Man and Dog

- nicholasjdenton

- Nov 17, 2023

- 13 min read

Updated: Nov 21, 2023

' 'Twill take some getting.' 'Sir, I think 'twill so.'

The old man stared up at the mistletoe

That hung too high in the poplar's crest for plunder

Of any climber, though not for kissing under:

Then he went on against the north-east wind -

Straight but lame, leaning on a staff new-skinned,

Carrying a brolly, flag-basket, and old coat, -

Towards Alton, ten miles off. And he had not

Done less from Chilgrove where he pulled up docks.

'Twere best, if he had had 'a money-box',

To have waited there till the sheep cleared a field

For what a half-week's flint-picking would yield.

His mind was running on the work he had done

Since he left Christchurch in the New Forest, one

Spring in the 'seventies, - navvying on dock and line

From Southampton to Newcastle-on-Tyne, -

In 'seventy-four a year of soldiering

With the Berkshires, - hoeing and harvesting

In half the shires where corn and couch will grow.

His sons, three sons, were fighting, but the hoe

And reap-hook he liked, or anything to do with trees.

He fell once from a poplar tall as these:

The Flying Man they called him in hospital.

' If I flew now, to another world I'd fall.'

He laughed and whistled to the small brown bitch

With spots of blue that hunted in the ditch.

Her foxy Welsh grandfather must have paired

Beneath him. He kept sheep in Wales and scared

Strangers, I will warrant, with his pearl eye

And trick of shrinking off as he were shy,

Then following close in silence for - for what?

'No rabbit, never fear, she ever got,

Yet always hunts. Today she nearly had one:

She would and she wouldn't. 'Twas like that. The bad one!

She's not much use, but still she's company,

Though I'm not. She goes everywhere with me.

So Alton I must reach to-night somehow:

I'll get no shakedown with that bedfellow

From farmers. Many a man sleeps worse to-night

Than I shall.' 'In the trenches.' 'Yes, that's right.

But they'll be out of that - I hope they be -

This weather, marching after the enemy.'

'And so I hope. Good luck.' And there I nodded

'Good-night. You keep straight on,' Stiffly he plodded;

And at his heels the crisp leaves scurried fast,

And the leaf-coloured robin watched. They passed,

The robin till next day, the man for good,

Together in the twilight of the wood.

Man and Dog is based on an encounter described by Edward Thomas in his penultimate Field Note Book. On Saturday 21st November 1914 he was walking up the Stoner Hill Road from home to his study at the top of the hangers, after lunch at 3pm. This was his normal route between Yew Tree Cottage (their last home in Steep which they had moved to in July 1913) and his study. It was a road he had got to know very well in the previous year or so. He called it New Stoner to distinguish it from the old coach road. Old Stoner, which had been the main route up the hangers before New Stoner had been built a century beforehand.

One of his earliest and best descriptions of New Stoner was from six years previously when he had written:

“New Stoner - great roaming spiral of road like a staircase or ascending balcony to view the vale.”

Written in the same era as Edward Thomas was writing, the Victoria County History, described the road “winding up the steep slopes of Stoner Hill with a skilfully engineered gradient through beautiful hanging beechwoods.” It went on: “It was laid out by private enterprise early in the last century (19th) in the expectation of a grant of the tolls on it, but this being refused by the government the promoters lost heavily by their undertaking.”

Thomas, as he began the climb up New Stoner that late November afternoon, overtook a man and his dog going the same way. The notebook has an extensive entry about their conversation as they walked up the hill together. The poem included much of this conversation though when he came to write the poem a couple of months later he omitted some of the detail. Thomas also included some additionally remembered - or imagined - particulars.

Some of the information in the notebook he omitted in the poem might have been because he thought they would diminish the man. This excising seems to have been of anything that would have detracted from this rustic, somewhat noble, almost heroic relic of Old England.

So when they meet at the bottom of the hill in the notebook Thomas and the man were not focused on the mistletoe in the poplars.

“Going up Stoner in cold strong NE Wind but a fine & cloudy sky at 3, overtook short stiff oldish man taking short quick strides - carrying flag basket & brolly & old coat on back & with a green ash stick in hand. Says it’s a fine day & as I passed (agreeing) he decides to ask me for ——- I don’t know, I stopped his request with questions, found him a 6d.”

Typically (and how very English!) when importuned for money, Thomas found a 6 penny coin to give the man and changed the subject, asking questions about the man's dog.

Later Thomas noted that the man might not reach Alton, his destination that night, because he had “rheumatism in one leg”. To “supple” the leg a bit he “rubs oil they sell at harness makers”. Again this is missing from the poem. As is the description in his notes of the man as having a ”round face with white bristles all over & eyes with red rims”. ET might have seen some of this as extraneous details when writing the poem. But as with the man's begging, he may also have not wanted to undermine the innate nobility he saw in such rural travellers, a breed of man which as he described at the end of the poem was disappearing.

On the other hand there were no mentions in the notebook of the poplar, mistletoe, or later the “flying man” falling from a tree. Most likely these were just omitted and recalled later when ET was writing the poem. Alternatively ET may have added in these from other sources or created imaginary excerpts to introduce the man more appropriately as a gentleman of the road and to give more colour to his character.

The original “flying man” was a German and an early pioneer of flight in the later 19th century. Flying men were also big attractions in the circuses of the time.

Poplars and mistletoes could be seen round the Ashford Hangers but they were especially common in the landscape round the Leadon Valley in Gloucestershire where ET had spent many weeks of 1914 to be close to Robert Frost, who had been encouraging him to write poetry. He went off there again a few days after the encounter with the man, actually following in his footsteps to the station at Alton early one morning to catch a train to Ledbury, managing to get a lift with a farmer in his cart.

Coincidentally, or not, Frost's influence is especially strong in Man and Dog with both speakers engaged in natural conversation in a country setting. Did ET note down this conversation expressly so he could write a poem about it? He was to use previous entries from much older notebooks for poems, when, at the time he noted them down, he had no plans to use them for anything except a possible prose piece. But the amount of detail from the notebook which he ended up using suggests this was planned - and he had examples of Frost's treatment of such subjects from his early poetry which he had so much admired.

He may have discussed the topic with Frost as a subject for a poem. Although there is no direct evidence of this, there is some interesting circumstantial evidence, when he had written to Frost about his "notebook stuff" early in their relationship.

In a letter of 19th May 1914 to Frost after asking "I wonder if you can imagine me taking to verse" he wrote: "I go on writing something every day. Sometimes brief unrestrained impressions of things lately seen, like a drover with 6 newly shorn sheep in a line across a cool woody road on market morning & me looking back to envy him & him looking back at me for some reason I cannot speculate on. Is this North of Bostonism (referring to Robert Frost's second book of poems)?" This encounter also occurred on the road down Stoner Hill - see the Walk section below for the complete notebook entry. So ET clearly had such an encounter in such a place in mind for a poem even in May 1914 many months before he started to write poetry. The Man and Dog provided fresh inspiration and, given this letter, one he may well have discussed with Frost.

After the embarrassment of the man’s begging, Thomas turned the conversation to the man’s dog, a Welsh sheepdog mix.

“He had a little bitch brown with spots of grey reminding me of a Welsh sheep dog - not much use, but company. He says the mother was almost pure (blue) Welsh. Hunts in Hangers, nearly got one this morn “he would & he wouldn’t, ‘twas like that”.

Edward Thomas would have known Welsh sheepdogs from his many travels in Wales, home of his forebears. They were good sheep dogs and also droving dogs, travelling long distances with drovers and their herds from Wales to English pastures and markets. The spots of grey were probably “blue merle” markings which the breed can be prone to - and the “pure (blue)” of her mother may be because she was a Blue Merle Hillman, an old breed, which has since died out.

The poem contains more detail than the note, describing the dog’s “foxy Welsh grandfather” with his “pearl eye” (cataracts) and “trick of shrinking off as he were shy,/Then following close in silence..”. In herding the Welsh sheep-dog had a “loose eyed action” not fixing the flock with its eye, unlike other sheepdogs such as collies.

In the notebook the man then went on: “They says these Welsh bitches will breed with foxes.” He recalled a Welsh sheepdog bitch he knew from the other side of Guildford, who had her litter of 7 in a rabbit hole. He had one of the the puppies which “used to bite anything it killed so hard it was useless: red mouth like a fox?(ET)”. The only remnant of this section Thomas retained in the poem was the “foxy Welsh grandfather”.

The notebook then turns to the man’s journeying across Southern England and through life, covering the same ground as the poem - Chilgrove, Alton, Christchurch, Southampton, soldiering with the Bedfordshires. The view to their right as they wound up the road provided a perfect backdrop to the man's recounting of his life, taking in a swathe of rural Southern England which the man had travelled and worked across. There was more detail in the notes of the man’s three sons at the front, “one just come from Bombay had nearly? finished his 8 yrs with the colours, one son a marine.”

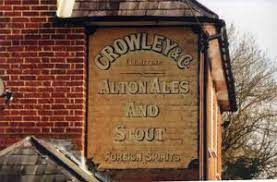

Because of his rheumatism the man was uncertain about reaching Alton that night, but he was more optimistic than in the poem of getting a “shakedown with a farmer” despite his dog. When he reached Alton he hoped to get a lift from “one of Crowley’s men to Longmoor to look for a job”. Longmoor was one of Hampshire's military camps on the heathland towards Surrey which was becoming a major training centre in the war. Crowley was the local Alton brewery, owned by the Crowley family who had become local landowners. So the men who the man hoped to get a lift from would most likely have been either draymen or farm workers.

The man went on to talk to ET about “the soldiers just coming to billet in Petersfield - he thought 2 or 3 thousand - 20, or so, in kilts - might be a Border Regiment.”

His guess was partially correct - the regiment was a Highland one. The 8th Battalion Seaforth Highlanders had been raised in September 1914 as part of Kitchener’s Second Army. It came to Petersfield in November from Aldershot before moving to Wiltshire camps in February 1915 for final training before embarkation to France in July. (In the post about March the 3rd, there is more detail on an encounter ET had with a couple of Seaforth Highlanders early in 1915 just outside his house at Yew Tree Cottage).

From this, the man's chain of thought in the notebook went to the men in France, as opposed in the poem to the link being his own plight not getting a shakedown because of the dog and having to sleep out, and his acceptance of that because “Many a man sleeps worse tonight/ Than I shall”. Again ET took another opportunity to shift the emphasis in the poem to the man’s innate nobility and stoicism.

The last we see of the man in the notebook was largely followed by Thomas in the poem, though shorn of some personal descriptive detail:

“A rustic, burring, rather monotonous speech, head a little hung down, but hardly a stoop as he keeps on at his stiff quick short steps among crisp dry scurrying leaves up to Ludcombe corner where I turned off.”

The leaf coloured robin was not mentioned that day in his notes but was there a couple of days later:

“23 xi

Robin is colour of twilight at 4.30 as soon as he leaves the ground & is seen in grey air among bare boughs over dead leaves & is invisible - you only know something moves, till he alights & is leaf coloured.”

The robin was a constant feature at the top of the road and by ET's study which he often noted. In a note of the previous year he had written of daws clacking in a flock and then dispersing at the top of New Stoner. He went on “But always a robin”.

The man was the latest of a number of countryside itinerants (farm workers, gypsies, tramps) ET had taken an interest in. Other characters included John Bower, the Umbrella man from the South Country and Jack Noman from the later poem May 23rd (who was in real life a tramp called Jack Rider who used to visit Thomas at his house).

Even in those days this type of character was passing, a disappearing species, with the beginning of modernisation of the agricultural world and the effect of the war. In the poem the man raised the topic of his own mortality - he knows he is too old to survive falling out of a tree again At the end of the poem ET picked up the theme again, contrasting the man’s passing for good with that of the robin which would return the next day, and every day throughout the year. Each year ET was always conscious whether he was seeing the last of the swallow, swift, cuckoo or a flower or leaves, before they departed or decayed after their season. But with the man (and Jack Noman), their departures were different from these seasonal comings and goings because ET believed they were permanent. Although in many ways these tramps and agricultural nomads were much more part of the natural world than their stay-at-home counterparts, they were becoming extinct. Once they were gone, there would be no others to replace them - something ET bitterly regretted.

A walk

The views from the road up Stoner Hill are still as impressive as ever, with near views over the Ashford Hangers and the fields of Ashford Farm and further away east across Stodham and Rake Common towards Blackdown Hill and Older Hill, and further south to the South Downs.

ET wrote of the near view from New Stoner in September 1913: “on the right you see with nothing but near beech boughs intervening the fields by Ashford Farm & tiny trees & cattle in soft sun, the road being shady & moist.”

The road up is a mile long from bottom to top, curving to left and then right round the steep yew and beech slopes above Ludcombe Bottom, the source of Ashford Stream. It’s impressive that ET managed to glean quite so much from the man on the walk up, even at the slower speed he would have had to adopt for the man to be able to keep pace with him.

Sadly a walk up nowadays is marred by the traffic on the road. In ET’s day the traffic was much more heterogeneous including steam tractors, stray sheep, the occasional tramp and farmers carts, and very few cars. In October 1913, he had come across a gaggle of men and animals coming down the road to Petersfield market as he was climbing up to his study (as he described in a letter to Frost - see above):

"At 9.15 marketers coming down Stoner 5 lowing big horned red steers - & small flock of yellow black faced sheep & a man behind with stick - a covered 4 wheel cart with a big heifer - a big waggon with several sheep, one lying down separated from rest by a hurdle - a trap with 2 big black pigs sticking up under net - winding slow & noisily down - the black whiskered men mostly silent."

At other times he delighted in the snow, the light at the the top of New Stoner after rain and the endlessly changing procession of trees and plants and their remnants through the seasons.

Sadly the path and bank which used to exist on the downward side of the road has long ceased to exist and pedestrians need to be very careful of the traffic as it speeds by. The road is best navigated by bike or car.

There are two parking places, one about half way up, one towards the top which afford good views east and south east. In late November when ET met the man and dog the leaves would have largely fallen from the trees so the views would have been less restricted than the glimpses snatched earlier in the year.

At Ludcombe corner where ET turned off, the path - the woodcutter's path - up from Ludcombe Bottom, far below, joins the road. Going down the deep path a few yards there is another path to the left up some steps which leads round the side of the hill eastwards, passing below the Edward Barnsley workshop (in ET's day Lupton's home and workshop), Lupton's copse, the Bee-House (ET's study) and the Red House (their second home in Hampshire). This was used by ET as a short cut to his study and an alternative to walking along Cockshott Lane, which is a little further on the right at the top of Stoner Hill.

A walk up or down the road needs to be conducted with great care. As touched on above, driving a car or riding a bike and stopping at the two parking spaces offer the best options to appreciate the road and its views. Towards the end of November, after most of the leaves have fallen, the near and far views are spectacular and immediately there are steep drops off the road with yews and beeches clinging to the slope (and sometimes toppled over). You can see why ET loved this road up to his study so much.

Acknowledgements/map

The OS map for Stoner Hill and the Ashford Hangers is OS Explorer OL33 Haslemere & Petersfield.

Field note books copyright Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection, New York.

I have also drawn on Edward Thomas's letter to Robert Frost of May 1914 from Elected Friends Robert Frost Edward Thomas to one another, edited by Matthew Spencer.

My thanks as always to Ben Mackay for editorial support.

Comments